System Design

Blueprint for Success: Navigating the Complexities of System Design Requirements as a Software Architect

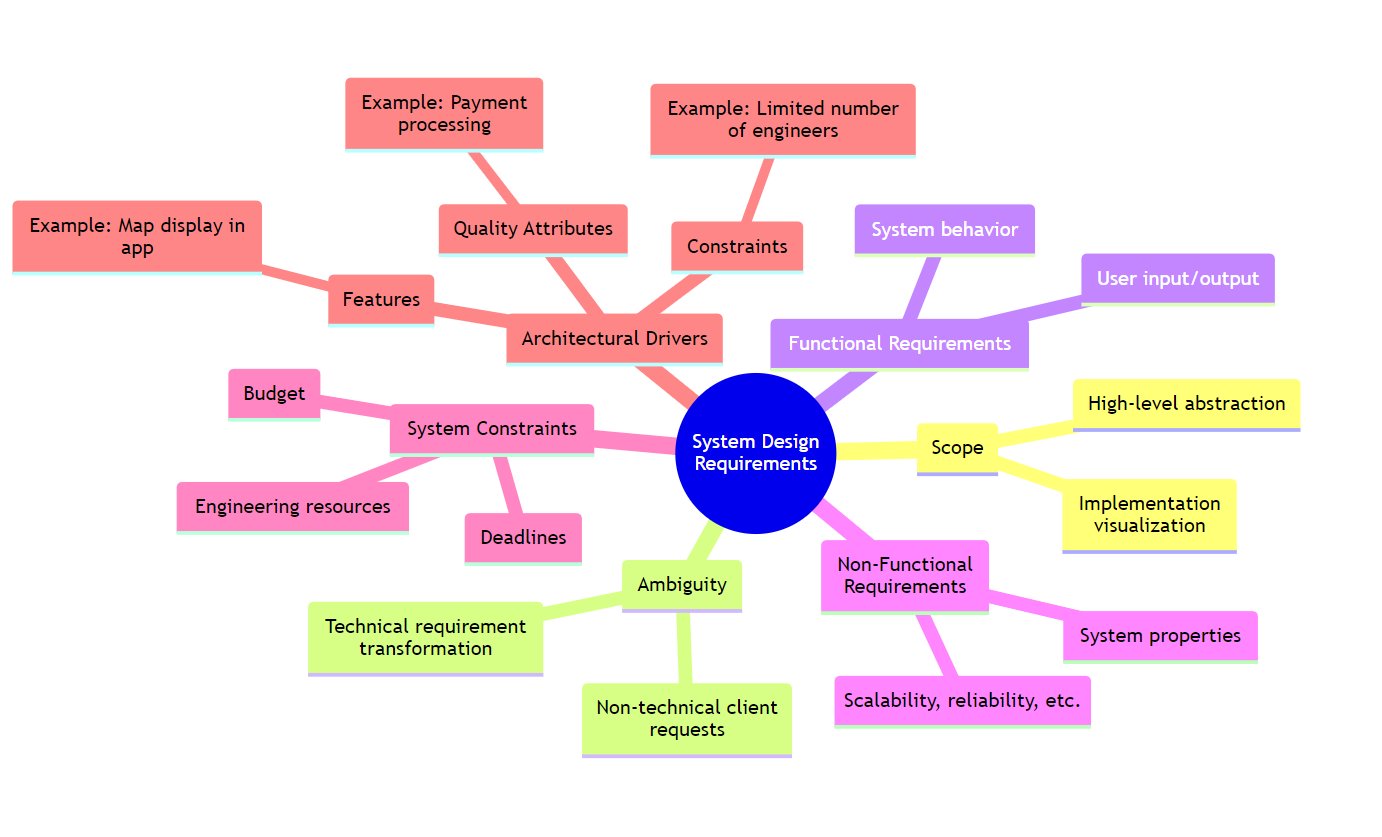

Introduction to System Requirements

System requirements might sound like a formal term, but at their core, they are about figuring out and narrowing down what we need to build for our clients. As software engineers, we're no strangers to informal requirements for tasks. However, designing a large-scale system brings unique challenges and differences from the usual requirements we encounter for smaller programming tasks.

The Scope and Level of Abstraction

When tasked with implementing a method or an algorithm, we usually have a clear understanding of the inputs and outputs. The scope is manageable, and we're often limited to specific programming languages. As we ascend to higher levels of abstraction, like designing a class, module, library, or an entire application, the range of potential solutions and the scope of the problem expand, making it harder to visualize the implementation.

Overwhelmed by Scale

Designing an entire system, such as a file storage system, a video streaming solution, or a cab service for millions of users, can be overwhelming. Where does one even begin with such a colossal task?

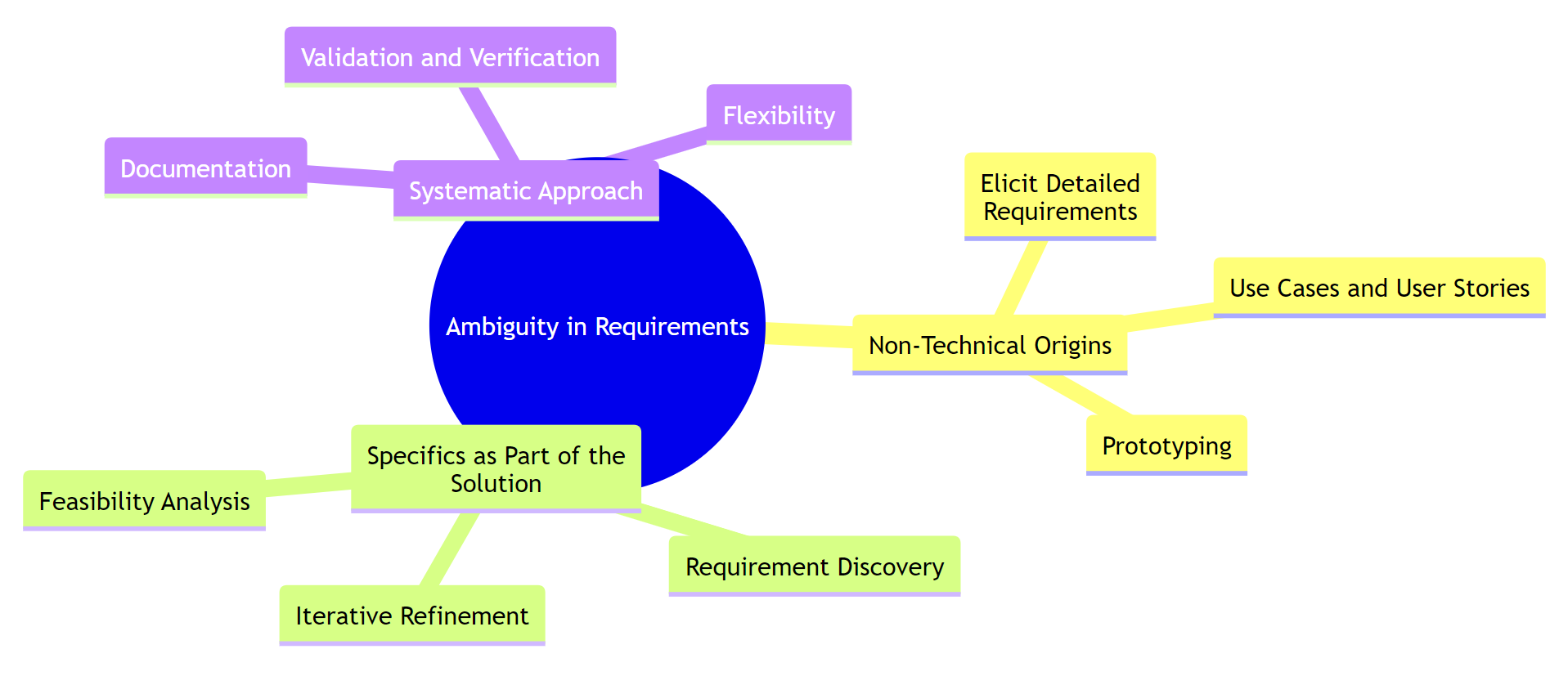

Ambiguity in Requirements

Ambiguity in system design requirements is a common challenge that software architects face. It can stem from a variety of sources, but two of the most prevalent are non-technical origins of the requirements and the inherent nature of the specifics being part of the solution itself. Let's delve deeper into these sources of ambiguity:

- Non-Technical Origins

When stakeholders are not well-versed in technical jargon or software development processes, they often communicate their needs in broad, high-level terms. For instance, a stakeholder might request a "user-friendly platform" without specifying what "user-friendly" means in the context of their user base or industry standards. It falls upon the software architect to engage in a dialogue that translates these high-level concepts into actionable, technical specifications. This translation process involves:

- Eliciting Detailed Requirements: Conducting interviews, workshops, and brainstorming sessions to extract as much detail as possible about the desired outcomes.

- Use Cases and User Stories: Creating detailed scenarios that describe how different users will interact with the system to achieve their goals.

- Prototyping: Developing a prototype or mock-up to visualize the concept, which can help in clarifying misunderstandings or misalignments in expectations.

- Specifics as Part of the Solution

Clients often approach architects with a problem rather than a solution. They may not know the technical possibilities or limitations that could influence the specifics of the system. In such cases, the architect's role includes:

- Feasibility Analysis: Assessing what is technically and practically feasible given the current technology landscape and organizational capabilities.

- Requirement Discovery: Asking probing questions that uncover deeper needs and potential features that the client may not have considered.

- Iterative Refinement: Working in iterative cycles to refine the requirements as more information is gathered and as the solution space becomes clearer.

In both cases, ambiguity can be mitigated by employing a systematic approach to requirement gathering and analysis. This includes:

- Documentation: Keeping a detailed record of all discussions, decisions, and agreed-upon requirements.

- Validation and Verification: Regularly reviewing the requirements with stakeholders to ensure they are still aligned with business goals and user needs.

- Flexibility: Being prepared to adapt the requirements as new information emerges or as the project evolves.

By addressing ambiguity head-on and establishing a clear, structured process for defining requirements, architects can lay a solid foundation for system design that meets the client's needs and is technically sound.

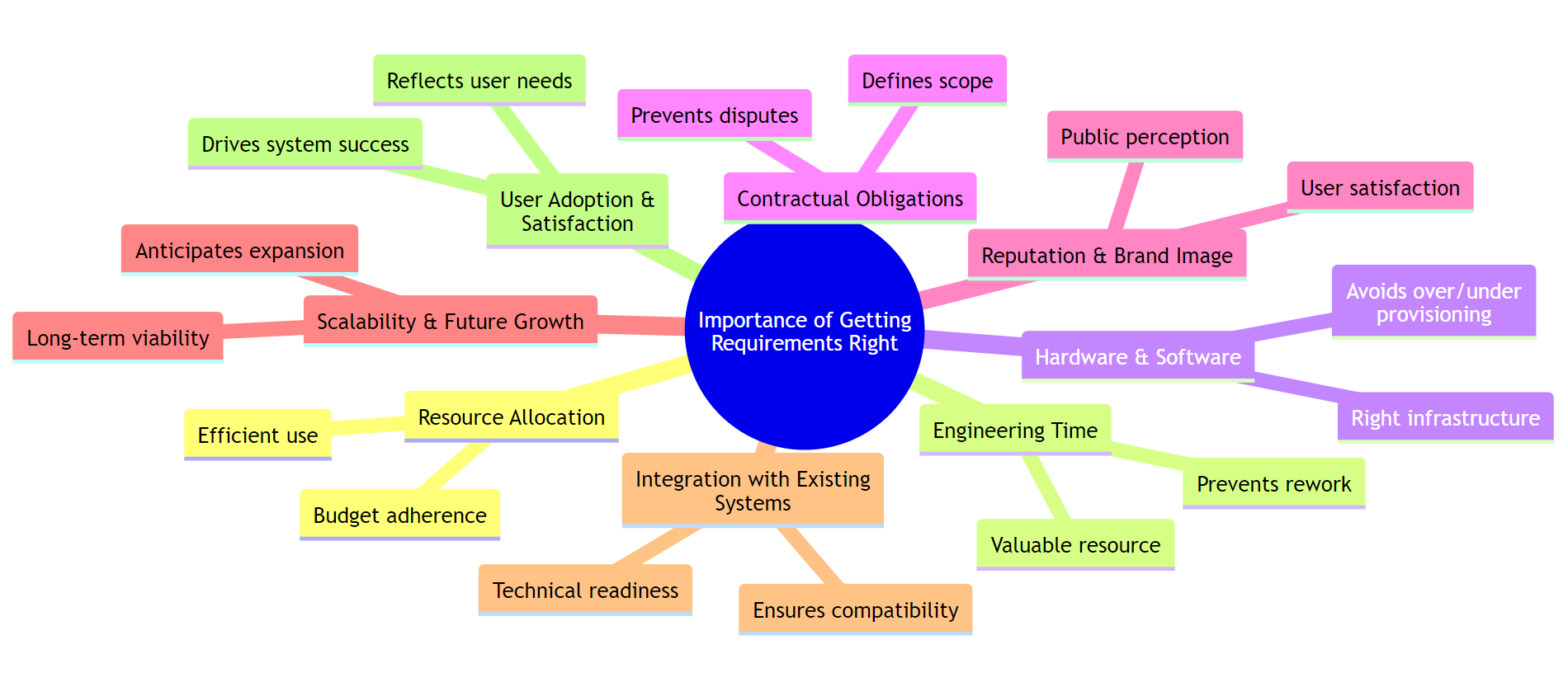

The Importance of Getting Requirements Right

The process of gathering and refining system requirements is not just a preliminary step in the development of software; it is a critical component that can determine the success or failure of the entire project. In the context of large-scale systems, the stakes are even higher due to the scale and complexity involved. Here's why getting the requirements right from the beginning is so crucial:

Resource Allocation and Budgeting Large-scale systems require substantial investment in both human and technical resources. Misunderstood or poorly defined requirements can lead to misallocation of these resources, resulting in wasted effort and budget overruns. Accurate requirements ensure that resources are allocated efficiently, keeping the project within budget and on schedule.

Engineering Time and Effort Engineering time is one of the most valuable resources in software development. In large-scale projects, the cost of engineering time is magnified due to the number of people involved and the complexity of their tasks. Getting requirements right helps in planning and can prevent the need for costly rework or redesign that can derail project timelines.

Hardware and Software Infrastructure Large-scale systems often require a significant upfront investment in infrastructure. This can include servers, networking equipment, and software licenses. Incorrect requirements can lead to under-provisioning (resulting in performance issues) or over-provisioning (resulting in unnecessary expenses). Precise requirements help in procuring the right infrastructure to support the system's needs.

Contractual and Legal Obligations Projects often come with contractual obligations with penalties for late delivery or failure to meet specified criteria. Accurate requirements are essential for defining the scope of work and deliverables in these contracts. Ambiguities can lead to legal disputes and loss of trust between parties.

Reputation and Brand Image The success of a large-scale system can have a significant impact on a company's reputation. Failure to meet user expectations can lead to dissatisfaction and negative publicity, which can be difficult to recover from. Conversely, a well-executed project can enhance a company's reputation for quality and reliability.

Scalability and Future Growth Requirements should not only address current needs but also anticipate future growth. Scalability must be built into the system from the outset. If the initial requirements do not consider future expansion, the system may become obsolete more quickly or require extensive modification to accommodate growth.

Integration with Existing Systems Large-scale systems often need to integrate with existing systems. Clear requirements are necessary to understand how these integrations should function and to identify any potential incompatibilities or technical challenges that need to be addressed.

User Adoption and Satisfaction Ultimately, the system must meet the needs of its users. Requirements that accurately reflect user needs and workflows are more likely to result in a system that users will adopt and find valuable. User satisfaction is key to the long-term success of the system.

In summary, the precision and clarity of system requirements are not just academic exercises; they are practical necessities that can significantly influence the efficiency, cost, and ultimate success of a software project. As such, software architects and project managers must give due diligence to the requirements gathering and analysis process, ensuring that all stakeholders have a shared understanding of the project's goals and constraints.

Classifying Requirements

Classifying requirements is a pivotal step in system design, as it helps architects understand what is expected of the system, how it should perform, and within what parameters it must operate. Let's delve deeper into each category:

Features of the System (Functional Requirements) Functional requirements are the most direct expression of what the system is supposed to do. They are the capabilities that the system must provide to the end-user or customer. These requirements are often captured as use cases or user stories that describe the system's interactions with users and other systems in detail. For instance, in a cab service system, a functional requirement might be the ability for users to book a ride through a mobile app. This requirement would detail the steps a user takes to enter their location, select a destination, choose a ride type, and confirm the booking.

Quality Attributes (Non-Functional Requirements) Quality attributes, often referred to as the "ilities," are characteristics that affect the user experience but are not about specific functionalities. They are about how the system performs certain tasks and include:

Scalability: The system's ability to handle growth, whether in data volume, traffic, or complexity. For a cab service, this means being able to serve more users as the service grows in popularity without degradation in performance.

Availability: The degree to which the system is operational and accessible when required for use. A high-availability cab service system ensures that users can book rides anytime without facing system downtimes.

Reliability: The system's ability to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period. Users expect the cab service to accurately track rides and process payments without errors.

Security: Protecting information and systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction. For a cab service, this includes safeguarding user data and transaction details.

- System Constraints Constraints are the non-negotiable limits within which the system must be developed. These can be due to technology limitations, regulatory requirements, budgetary restrictions, or resource availability. For example, a cab service might need to be developed within six months to meet a strategic market window, or it might need to comply with data protection regulations specific to the regions it operates in. Understanding and documenting these constraints is crucial because they often dictate the trade-offs that architects and developers will need to make. For instance, if the budget is limited, the system might start with supporting only the most critical quality attributes, with plans to enhance others over time.

By thoroughly classifying and understanding these requirements, architects can ensure that the system they design will not only meet the current needs but also be adaptable to future demands and changes in the operating environment. This foresight is essential in creating a system that is robust, flexible, and delivers long-term value to users and stakeholders.

Expanding on Functional Requirements with Examples

Let's dive deeper into functional requirements using our cab service as an example. Suppose the client's vision is a platform where riders can easily find and book a cab. A functional requirement here could be the ability for riders to book rides in real-time. For instance:

Example Functional Requirement: The system must provide a real-time booking feature for logged-in riders, showing all available cabs within a 10-mile radius. This requirement dictates that when a rider logs into the app, they should immediately see available cabs. The input is the rider's current location, and the output is the updated list of cabs.

Illustrating Non-Functional Requirements with Scenarios

Non-functional requirements often dictate the quality and performance of the system. For example, our cab service needs to be reliable and performant under heavy loads.

Example Non-Functional Requirement: The system should support at least 100,000 concurrent users with a response time not exceeding 2 seconds. This requirement ensures that during peak usage, the system remains responsive and efficient, providing a seamless experience for all users.

System Constraints and Their Impact

Constraints can significantly shape the final design of a system. For instance, if the cab service needs to be launched within six months, this constraint will influence many architectural decisions.

Example System Constraint: The system must be ready for a public beta test in six months, with a limited budget that precludes the use of certain expensive technologies. This constraint may lead to the selection of a more cost-effective technology stack or the decision to prioritize certain features over others for the initial release.

Real-World Implications of Requirements

Understanding the real-world implications of these requirements is crucial. For example, the functional requirement of real-time booking implies the need for a robust backend capable of handling frequent location updates from cabs. It also suggests a need for a scalable database that can quickly query and return cab availability within a specific radius.

The non-functional requirement of high concurrency support indicates the need for a load balancing solution and possibly a distributed architecture to ensure responsiveness.

The time constraint means that the architecture must be simple enough to be implemented quickly but flexible enough to scale for future growth.

Bridging the Gap Between Requirements and Implementation

As software architects, it's our responsibility to bridge the gap between high-level requirements and practical implementation. This involves making informed decisions about the architecture, technologies, and frameworks used to build the system.

Bridging Example: Given the requirement for real-time updates, an architect might choose a publish-subscribe model using WebSockets for efficient, bidirectional communication between the server and clients.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Requirements

In conclusion, the art of gathering and analyzing requirements is a critical skill for software architects. It involves understanding not just the technical aspects but also the business context and user needs. By classifying requirements into functional, non-functional, and constraints, architects can create a focused and effective design. Real-world examples like our cab service illustrate how these requirements translate into architectural decisions that ultimately shape the success of the system.

As we continue to explore the intricacies of system design, remember that each requirement is a piece of the puzzle. It's the architect's job to fit these pieces together into a cohesive and efficient whole that meets the client's vision and stands the test of time.